For the curious, overwhelmed mind, here’s how to research health topics and find clarity without getting lost.

Key Takeaways

- Start with clear, neutral questions instead of chasing quick answers.

- Vet the source, claim, and evidence before believing health information.

- Learn to spot red flags of AI content, deepfakes, and emotional manipulation.

- Cross-check multiple institutions to build confidence in your findings.

- Use a small, trusted research toolkit (NIH, Cochrane, PubMed, Harvard, UCLA, Oxford, etc.).

The Maze We’re All Walking Through

You feel a twinge of worry, open a search tab, and, boom, there’s a viral video of a “doctor” praising a miracle supplement, a dozen contradictory blog posts, and a sponsored “review” that reads like an ad.

Add AI-generated content, deepfakes, and algorithmic hype, and even smart people can feel outmatched.

This guide turns that chaos into a process. You’ll learn how to ask better questions, vet sources, spot AI/disinformation red flags, and build a small, trustworthy toolkit you can use again and again.

Important: This article is educational in nature and should not be considered medical advice. Use it to prepare for conversations with a qualified clinician.

Step 1: Start With the Right Question (and Neutral Language)

Clarify your aim:

- Symptom: “What are common, non-emergency causes of ___, and when should I seek care?”

- Treatment: “What are evidence-based options for ___ in adults? Benefits, risks, typical timelines?”

- Wellness: “What lifestyle habits have moderate-to-strong evidence for improving ___?”

Use neutral phrasing to avoid confirmation bias.

Instead of: “Proof that Product X works”

Try searches like:

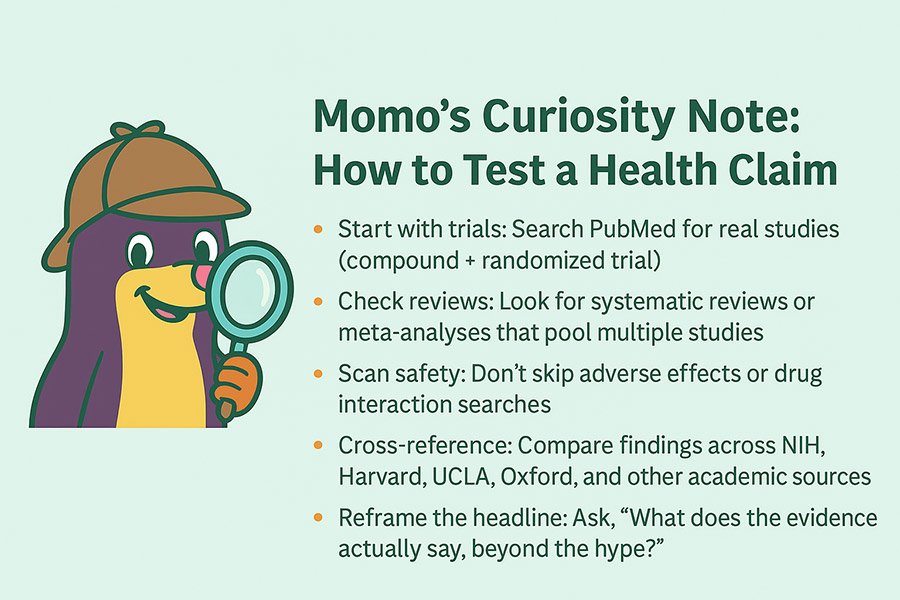

- “systematic review [compound/condition]”

- “randomized trial [compound/condition]”

- “adverse effects [compound/condition]”

- “long-term outcomes [compound/condition]”

- “meta-analysis [compound/condition]”

For example:

- systematic review magnesium l-threonate cognitive function

- randomized trial ashwagandha anxiety

- adverse effects intermittent fasting women

- long-term outcomes melatonin adolescents

Example meta-analysis searches:

- meta-analysis omega-3 fatty acids depression

- meta-analysis probiotics irritable bowel syndrome

- meta-analysis vitamin D bone density older adults

Step 2: Map the Information Landscape

Not all sources do the same job.

- Primary research: PubMed, Cochrane reviews, ClinicalTrials.gov.

- Secondary/interpretive sources: Major hospitals (Mayo Clinic, Johns Hopkins), government sites (NIH, CDC, WHO), and leading academic medical centers like Harvard Health, UCLA Health, Columbia, NYU Langone, USC Keck, Oxford, and Cambridge. These institutions publish patient-friendly research summaries and news that are grounded in peer-reviewed science.

- Commercial/consumer content: Product pages, influencers, forums—helpful for experiences, but always verify.

Step 3: Vet the Source, the claim, and the Evidence

Source: Who wrote it? What’s their funding? Do they cite real studies?

Claim: Is it specific? Balanced? Clear about limits?

Evidence: Is it based on systematic reviews or just anecdotes?

Step 4: Red-flag Radar for AI & Disinformation

Watch for:

- Deepfake cues: Mouth doesn’t match audio, strange blinking, or “doctors don’t want you to know.”

- AI text tells: Generic phrasing, confident tone without data, fake citations.

- Manipulation tactics: Overblown promises, urgency, “miracle cure” language.

Step 5: Triangulate

Never rely on one source. Look for convergence across independent bodies.

It’s also important to note that even long-established institutions like the CDC or NIH are not immune to controversy. Recent events at the CDC have reminded us that communication from these organizations can be shaped by pressures beyond pure science. That doesn’t mean the underlying research is invalid — but it does mean we should apply the same vetting process here as we would anywhere else.

Ask:

- Does the institution cite and link to the original data or peer-reviewed studies?

- Are independent organizations (universities, professional societies, international bodies like the WHO) reaching similar conclusions?

- Is there a difference between the science itself (datasets, surveillance reports, technical papers) and the public-facing policy messaging?

In short: don’t blindly trust or dismiss — verify the specific claim. This keeps you balanced: respectful of scientific work, but alert to how it’s communicated.

If Harvard Health, Oxford University, and Mayo Clinic all align and cite overlapping peer-reviewed studies, you can be far more confident.

Additionally, distinguish between science and policy: datasets and peer-reviewed papers are often more reliable than press releases or headlines.

Step 6: Practical reading skills

Quick scan checklist:

- Abstract → population, intervention, outcome.

- Methods → randomized, blinded, sample size.

- Results → absolute change, not just percentages.

- Limitations → are they acknowledged?

- Discussion → avoid overgeneralization.

Step 7: Build a Trusted Toolkit to Research Health Topics

Start here

Please note that the following URLs can change.

Here is the list of trusted health resources with their corresponding URLs:

• NIH Office of Dietary Supplements – Fact Sheets: https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/list-all/

• FDA Safety Communications: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/safety-communications

• Cochrane Library: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/

• PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

• ClinicalTrials.gov: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/

• Mayo Clinic: https://www.mayoclinic.org/

• Johns Hopkins Medicine: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/

• Harvard Health Publishing: https://www.health.harvard.edu/

• UCLA Health: https://www.uclahealth.org/

• Columbia University Irving Medical Center: https://www.cuimc.columbia.edu/

• NYU Langone Health: https://nyulangone.org/

• USC Keck Medicine: https://www.keckmedicine.org/

• Oxford University Medical News: https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/science

• Cambridge University Health Research: https://www.cam.ac.uk/research/research-at-cambridge/life-sciences

Step 8: Decision-making You Can Live With

Before acting, draft a short “decision brief”:

- My question

- Best evidence found

- Benefits I care about

- Risks/costs

- Alternatives

- Plan to discuss with clinician

Step 9: Example of How to Research Health Topics in Action

The Claim

“Magnesium l-threonate improves memory.”

This is the kind of simple, confident statement people see in ads, blogs, or even TikTok videos. It sounds compelling — but is it true?

The Search Path

- PubMed trials

Search:magnesium l-threonate cognitive function randomized

→ PubMed lists peer-reviewed studies. Here you’d see small clinical trials testing magnesium l-threonate on memory and cognition. Results are mixed — promising, but far from conclusive. - Systematic reviews

Search:systematic review magnesium cognitive aging

→ A systematic review pools results across multiple studies. Reviews may not single out l-threonate yet (it’s newer), but they summarize broader evidence on magnesium and cognition. - Adverse effects

Search:magnesium l-threonate adverse effects interactions

→ Even if a supplement “works,” it may have downsides. Safety checks show mild GI upset, possible drug interactions, and supplement quality concerns. - NIH fact sheet

Resource: NIH Office of Dietary Supplements – Magnesium Fact Sheet

→ Provides clear guidance on daily intake, safety, and forms of magnesium. The fact sheet does not highlight l-threonate as proven for memory. - Harvard Health / Johns Hopkins summaries

Resources: [Harvard Health Publishing], [Johns Hopkins Medicine]

→ Consumer-friendly articles that acknowledge early interest in l-threonate but caution that evidence is preliminary and more research is needed.

Why This Matters

By the end of this trail, the confident headline becomes:

- Evidence: A few small, early trials show promise but no consensus yet.

- Risks: Mild side effects possible; supplement quality varies.

- Alternatives: Stronger, proven supports for memory include sleep, exercise, and diet.

- Decision: Worth a conversation with your clinician if you’re interested — but not a miracle cure.

Step 10: Reusable Checklist

Before you believe a health claim, confirm:

- Straightforward, neutral question.

- Found at least one systematic review or guideline.

- Checked adverse effects/interactions.

- Cross-referenced across independent sources (Harvard, Oxford, Mayo, etc.).

- Confirmed date, population, and outcome relevance.

- Have a plan to reassess.

From Overwhelmed to Empowered

You don’t need to be a scientist to research health topics like an expert. You need a repeatable method: ask good questions, verify your sources, identify synthetic “noise,” and make informed choices.

That’s the modern health detective mindset: curious, skeptical, and empowered.